Why do you need a problem typology model or framework such as Cynefin? Well, have you ever had a problem that, in trying to solve it, you have made it worse?

You thought you could fix that device, but it stayed broken. Or you stepped into an argument when the resolution seemed obvious, but your intervention just created further hostility. Or perhaps you were a bit lost, and you thought you had found a route out, but then things got worse. We have all been there, right?

When trying to solve problems we make things worse when we don’t properly understand the problem in the first place. Therefore, one critical step in decision-making is classifying the type of problem that you are trying to solve. This is important as – if you fail to categorise the nature of your challenge – you could end up applying the wrong solution or approach. This might not only fail to solve the issue, but it could also make it worse.

When things go wrong

“It’s the wrong trousers Gromit, and they’ve gone wrong!”

Wallace and Gromit

I got to see this happen on an organisational level when I was asked to help a large local government in the UK. The institution was falling into disorder but no one within the organisation could agree on why. The lower-level managers thought it was a simple problem. They knew how to deliver services; it was just that the demand had gone up and finances had gone down. All they thought they needed was more money. This mindset was pushing the institution further towards the brink of chaos and a crisis for the whole organisation.

The high-level management thought it was a complicated issue, hence bringing in consultant ‘experts’ such as me to analyse and resolve the problem. They assumed that efficiency was the biggest issue and, therefore, wanted to focus (almost exclusively) on finance. We, the outsiders, could see that it was a complex challenge. The situation was changing rapidly and was not going to reverse; the managers at all levels were looking at the problem in the wrong way. So, we introduced models to help change the way everyone – at all levels – viewed the issues and encouraged broad engagement to come up with creative solutions. It was not an easy process, but identifying the nature of the problem was the first step.

Free Personal Leadership Action Plan

Just sign up here to receive your free copy

Understanding complexity and problem typology

The process of identifying the problem typology is the sphere of complexity science. Understanding complexity is a growing academic field that has important implications for leadership and decision-making.

Complexity is, well, complex, but fortunately, some models and frameworks bring the concepts of complexity, leadership and choice together; to help us understand obstacles and assist in choices.

As a leader, I regularly use Keith Grint’s model that classifies problems as either tame, critical or wicked. Understanding the problem then informs the method of influence to use, be that managing tame problems, providing command for critical issues or leadership for wicked issues.

This idea of matching leadership approaches to types of problems is not confined to the Grint model. There is another model that I have also found very insightful, particularly for understanding complex challenges, which is the Cynefin framework.

“Circumstances change, however, and as they become more complex, the simplifications can fail. Good leadership is not a one-size-fits-all proposition.”

Snowden and Boone

The Cynefin framework

This other favoured model is the Cynefin framework. It was created by Dave Snowden and further developed in partnership with Mary E. Boone. The word Cynefin comes from the Welsh language and alludes to a sense of place. In other words, we need a sense of place to understand our challenges.

The framework gained acclaim and awards, particularly after the publication of A Leader’s Framework for Decision Making, in the Harvard Business Review. It has been adopted and used not only by corporations but by governments, for example by the US government in counterterrorism and the National Health Service in the UK.

This model is slightly more complex than Grint’s but the framework allows deep thought into both the classification of problems and how problems can evolve (or crash) from one domain into another, depending on how we address them.

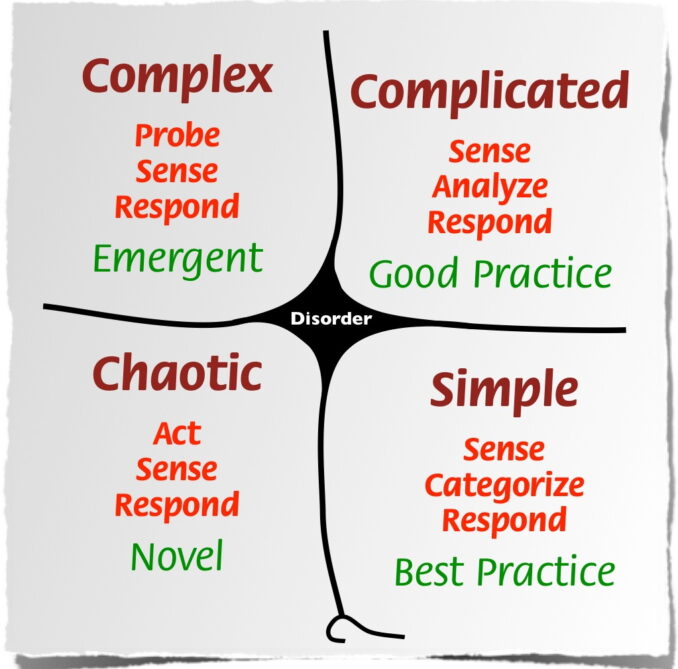

The framework is based upon classifying the complexity of issues into the following four types of problems and five domains:

- Clear

- Complicated

- Complex

- Chaotic

- Disorder (uncategorised problems)

The Cynefin Framework – wikicommons

Clear problems

The clear domain (also known as either the simple or obvious domain) refers to problems that have known solutions. Here, when it comes to information and assumptions we are in the realm of “known knowns”. Therefore, we identify (sense), categorise, and then respond to these problems with known solutions. Use best practice when the cause-and-effect relationships are obvious.

Clear problems are generally heavily process-driven. The process is clear, measurable, and therefore relatively simple to manage. Examples of these clear problems could be applying for a personal loan or mortgage or manufacturing a common item on a production line. When I worked in the construction industry, most house-building fell into this category. It is easy to get pre-made plans for homes.

The danger with clear problems is complacency. When using a known solution, it is easy to fall into that habit and apply the same practice again and again, but then fail to notice how the situation is changing. If the situation changes too much, then applying the old solution could push the problem into disorder or the chaotic realm. This was what was happening with the local government I mentioned earlier.

This can also happen when people assume a problem has a clear solution, but the known knowns turn out to be wrong assumptions. This sort of mistake is covered in How to Identify and Disarm Wrong Assumptions.

Complicated problems

Complicated problems are the domain of experts. Here the “known unknowns” are sensed but then need to be analysed before any response, because there may be multiple solutions to the given challenge. These solutions, if successful, may then go on to become best practices, and the problem moves from the complicated realm to the clear.

“Complicated” is the realm where the professionals – such as lawyers, engineers, and doctors – earn their living. A deep knowledge of first principles, coupled with the proper experience, allows specialists to find options and solutions. Again, reflecting on my experience as an engineer, house-building per-se was a simple problem but developing new sustainable construction techniques – for example reducing the amount of concrete and steel we rely upon – is a complicated problem.

The danger in this realm is that experts can be blinkered, which can stifle novel approaches. For good solutions, there should be an environment that challenges existing thinking and encourages new ideas, through a diversity of people and inputs.

Leadership Development: Master the Top Leadership and Life Skills

Better lead in life and work to maximise your success. Sign up and access materials for free!

Complex problems

Complex problems exist in environments that are constantly changing, with multiple factors at play. Here we are in the realm of “unknown unknowns” as things are in flux and there are just too many things to identify or measure. These problems can also be of the “wicked” variety where problems may need least worst solutions as there are no “good” ones.

The complex realm is the land of emergent ideas. Problems in this space require true creativity. Many entrepreneurs and start-ups naturally fall into this sphere, but even large businesses and institutions find themselves in this space due to the increasingly congested, connected and fast-changing world we live in.

Traditional top-down, command and control, management styles fall short in complex situations. Complex problems require a more experimental approach. The problem needs to be probed, then sensed to develop a new response.

New management techniques have emerged to deal with these complex situations. Eric Ries (author of The Lean Start-up) popularised the idea of developing a minimum viable product as the basis for experimentation. Agile project management has also taken over from traditional project management to address fast-changing situations.

Chaotic problems

In chaotic situations, there is no order and therefore no obvious cause and effect relationships. Here a sense of order needs to be imposed and therefore a leader needs to act carefully but decisively. These situations are like the “critical” issues of the Grint model that require a more directive, command leadership approach.

Large crises fall into the chaotic realm, such as the events of September 11, 2001. On a smaller scale, I have experienced these sorts of emergencies while on operations or even when alpine climbing. Here the approach required is to act first, then sense how things change, and then respond with appropriate next steps to lead out of the crisis.

Disorder

The realm of disorder represents the space where it is unclear where a problem exists. If you feel completely lost, then you are likely to be in this realm! Here it is likely that the problem has not been properly understood or that the challenge has aspects that sit in multiple domains.

So, the best approach when facing disorder is to gather data to better understand the issue and then break down the problem into constituent parts so that each element can be dealt with in its relevant domain.

A summary of how to apply the Cynefin framework

The world is more irrational and unpredictable than we would like to admit. It is therefore vital that we properly identify the nature of the problems we face to take the right approach to solve them. This is particularly important for leaders who are responsible for spotting challenges and then flexing their decision-making approach and management style.

Models can help us do just that and the Cynefin framework shows us that:

- When the problem is clear and the solution known, find and apply best practices

- If the issue is complicated, then expertise can find solutions from first principles

- When the environment is complex, emergent ideas can be found through experimentation

- In chaotic situations, a rapid response is needed to establish some order

- When there is disorder, break down the problem further to assign each part to the realms listed above.

And remember:

“Expect problems and eat them for breakfast.” – Alfred A. Montapert