Can you remember a time when your pulse was racing at work? Perhaps you recall a moment when you went red in the face in a meeting or needed to stop and take some deep breaths. Maybe you felt tense when being told of a task or broke a sweat trying to beat a deadline.

These physical reactions are common and were most likely linked to emotions such as fear, frustration, or anger. Most people experience this kind of agitated psychological state at some time or another in their jobs. These physiological, fight-or-flight responses, still manifest even though relatively few people’s professions involve a threat to their physical person.

And that can be a problem as these experiences can have a negative impact on cognition. Something that feels unfair can derail you. Feeling isolated can reduce productivity. Being disempowered undermines creativity and decision-making. Concerns about job security make it hard to concentrate.

So why does this fight-or-flight response kick in and what can we do about it?

Fight or flight, reward, and threat

The fight-or-flight response was first described by Walter Bradford Canon in 1915. It is also referred to as, the fight, flight, freeze or fawn response, but the basic physiological and neurological aspects are the same in all cases.

Our neurobiology dictates our responses to external stimuli. In other words, our brains are wired to react in certain ways in certain circumstances. If we perceive a situation to be rewarding, we will act in one way, if we find it threatening, we will respond in another.

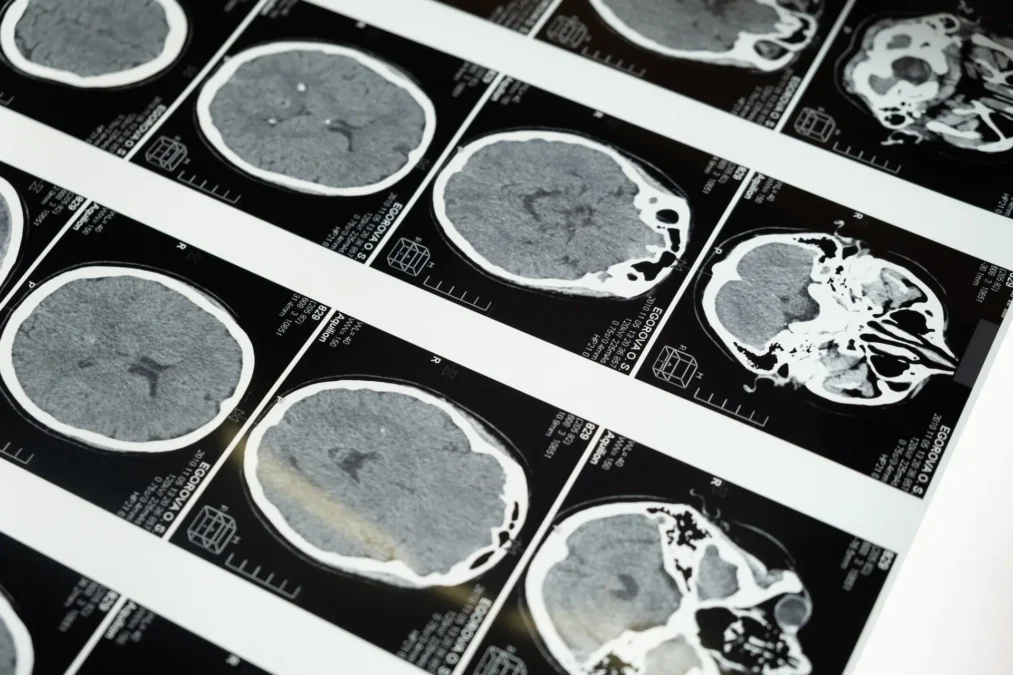

The fight-and-flight reaction is primarily there to help us survive physical threats. This human behaviour is similar to many animal species’ responses and is triggered within the amygdala, one of the oldest parts of the brain (in evolutionary terms).

Free Personal Leadership Action Plan

Just sign up here to receive your free copy

The Amygdala hijack

Interestingly (but often unhelpfully), even with the scarcity of sabre-tooth tigers in the office, these fight-or-flight responses are initiated by our social interactions. And the problem with this is the threat of amygdala hijack; where one part of the brain overrides the functions of other parts of the brain as it pumps stress hormones into the body.

Amygdala hijack happens when the amygdala interprets something as threatening and then sends a signal to the hypothalamus, the brain’s command centre. The hypothalamus then stimulates the sympathetic nervous system which activates the adrenal glands, pumping epinephrine (adrenaline) into the bloodstream. This adrenaline prompts physical effects such as expanded airways, an increased pulse and heightened heart pressure. Senses – such as sight and hearing – are sharpened and sweat glands are opened. The epinephrine also starts a release of glucose and other nutrients into the bloodstream.

These changes impact other parts of the brain. The frontal lobes, the areas of the brain that deal with reasoning, decision-making, planning and evaluating emotions, can be temporarily crippled. The amygdala overrides the frontal lobes if it perceives something as a significant threat. When this happens, our responses become more primal and less rational.

All these things prepare the body for action; to fight or to run away. This is useful if you are stepping into a boxing ring or up to compete in a race, but slightly problematic if you are stepping up to give a presentation or to meet a new client. So what can we do?

The best way to manage those physical symptoms is by taking some deep breaths. This will allow the initial flush of hormones to pass and for our rational minds to clear. Next, we can diagnose the cause of the symptoms by considering the social triggers.

YouTube Video: Fight or Flight and Amygdala Hijack

What is the SCARF model and who created it?

The SCARF model summarises the main social circumstances that prompt reward or threat responses. The SCARF model was invented by David Rock, author of Your Brain at Work. David Rock developed the tool using the latest insights from neuroscience and psychology.

The letters in the SCARF model stand for:

- Status

- Certainty

- Autonomy

- Relatedness

- Fairness

These are all concepts that can trigger feelings of reward or threat in social engagements.

We move away from what we perceive as threatening situations, either consciously or unconsciously. These are the ones that trigger the fight-or-flight response. By contrast, we are drawn towards situations of potential reward. So, the elements of the SCARF model prompt either toward or away behaviours, depending upon the context.

Here is a fuller explanation of each element in turn:

Status

Status is about where people feel they are in the pecking order. It is about power but also about recognition.

Certainty

Certainty is all about how well we feel we can predict the future. It relates to predictability in our lives and minimising unexpected changes.

Autonomy

Autonomy is the feeling of having choices and being empowered to make decisions. It makes us agents of change, rather than change being forced upon us.

Relatedness

Is about feeling safe in our relationships and is tied to concepts of trust and trustworthiness. We are drawn towards being connected with others and fear being isolated or ostracised.

Fairness

Fairness is how we feel about our exchanges and interactions and whether we consider them equitable.

Leadership Development: Master the Top Leadership and Life Skills

Better lead in life and work to maximise your success. Sign up and access materials for free!

An example of applying the SCARF model

Here is a painful personal experience explained using the SCARF model. It is one I can still vividly remember, as I was triggered across all the zones of the SCARF framework. It happened when I was a young Army Officer.

I was a Lieutenant on a training exercise, and even though I did not have my own platoon or troop at that point I had been preparing to lead a team for the deployment. Initially, for the exercise, I had not been given a defined role, so I worked to find areas where I could add value and take responsibility.

Then, just before the final phase of the exercise, my commanding officer – who obviously had formed a low opinion of me – informed me that I was not going to be a platoon leader. Instead, I was assigned as the deputy of a section (a smaller team). When I received the news, I was shocked. My whole body went tense, and red mist clouded my thoughts.

SCARF diagnosis:

My status was undermined. I am not obsessed with rank or position but here I suffered the shame of being publicly demoted. My line manager had deliberately pushed me down. I felt demeaned.

The certainty I had about what I was doing was taken away. The role I had been preparing for was taken from me and I even started to fear for my future in the military. If this was how my senior officer rated me, what was I even doing as an officer in the army?

My autonomy was eroded. The plans I’d made had been trashed and now my decision-making capacity had been reduced further due to being put in a junior position.

My relatedness to my colleagues and those in my team was also negatively impacted. Everyone could see what had happened and this made relationships uncomfortable. It was particularly awkward for the junior manager who now nominally had me under his authority. The whole team dynamic was undermined.

And the whole situation went against fairness. I did not feel I deserved to be humiliated in this way. It was also not fair on the team I was been assigned to.

At the time I wanted to either punch someone or run away. Fortunately, circumstances intervened, and I was called away to other duties, but the whole experience knocked my self-confidence in a way that took a long time to recover. I was left feeling bitter and stressed.

Use the SCARF model to understand and improve your social interactions

So next time you step into a social situation apply your neuroleadership (your new understanding of neuroscience and leadership) and remember the SCARF model. How do the various social interactions make you feel? How are you drawn towards some people and away from others?

If you feel your body moving into fight-or-flight mode (but you are not physically threatened), take a few deep breaths and then diagnose the cause. Is your status threatened? Do you feel a lack of certainty, or perhaps reduced autonomy? Is the situation eroding your relatedness or your feelings of fairness? What might you do to restore your balance?

If you are a manager planning a meeting with a subordinate, consider how the SCARF elements might impact the other person. Make sure the person feels valued (status), unflustered (certainty), that they have choices (autonomy), they are part of a team (relatedness) and are being treated well (fairness)