Management guru Peter Druker reportedly said “culture eats strategy for breakfast”, but other leaders and strategists express similar sentiments. The underlying message is, it does not matter how good a plan you have, if you don’t consider the human element then your strategy is unlikely to succeed.

Having worked with numerous companies on developing a strategy it can be all too obvious when grand plans are doomed to failure. One key metric is the delta between a company’s stated values and the behaviour of the people within the organisation. But to address this gap you first need to understand the organisational culture.

Why strategy fails

A strategy is a plan of action to achieve a long-term goal. As Richard Rumelt notes in his book Good Strategy Bad Strategy, a good strategy must diagnose the challenge to overcome, create a guiding policy to address that challenge, and then produce coherent actions that ensure that the policy is carried out.

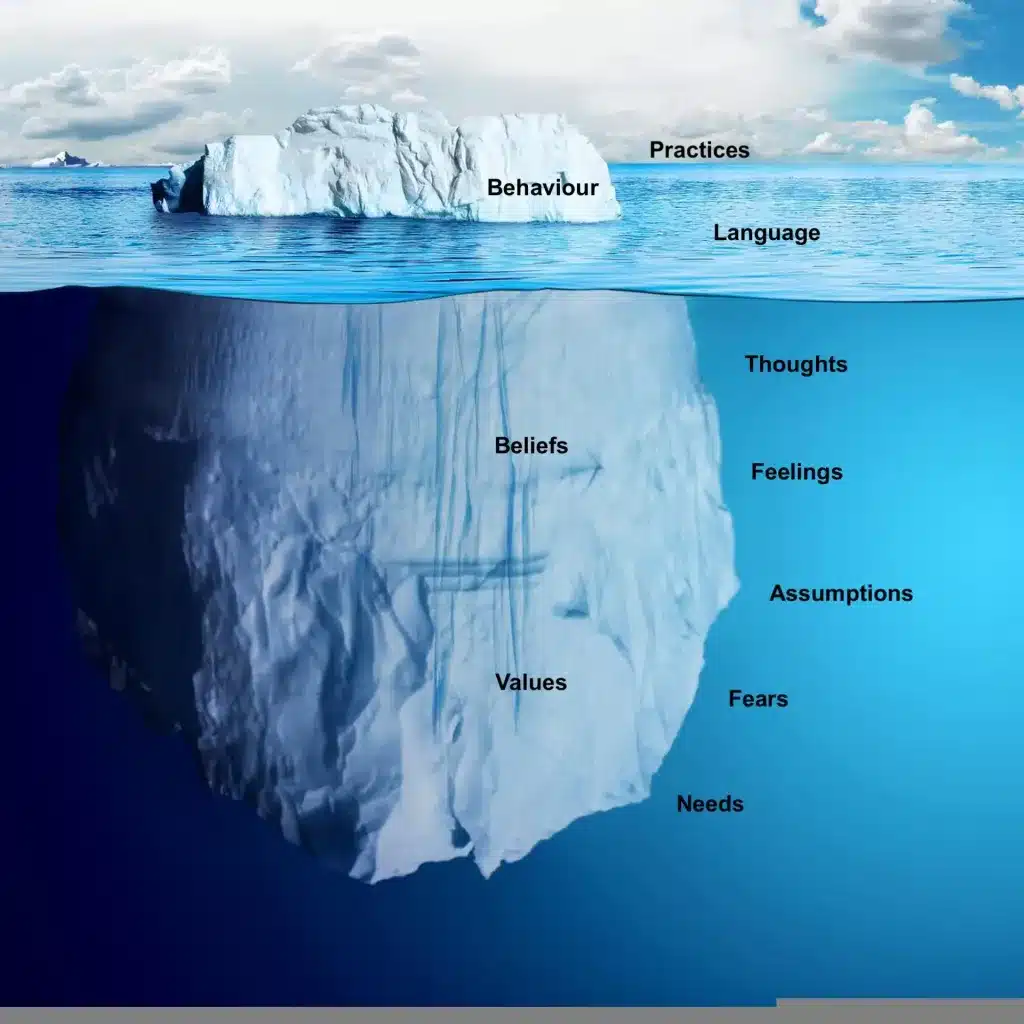

Most people get the essentials of what strategy is. Where it generally fails is in the third element, the implementation; ensuring people carry out the actions is where things go wrong. This is often because the board level strategists fail to take culture and values into consideration. Actions are just behaviours, but real change is not brought about by one single action. It is the compounding effect of multiple actions over time. If you want to shift the way you want people to act you need to change their normal routines.

Routines are just one element of organisational culture. Changing our personal habits can be difficult, so why – do leaders – expect to change a whole organisation and the habits of hundreds, if not thousands of people, just because they say so? Making this sort of transformation requires careful consideration and to make a change in behaviour you first need to understand all the facets of the culture of a given group.

The importance of understanding organisational culture

Every group of humans has a culture of some sort. Every family, company, and sports team – let alone a country or nation-state – has its own culture. The problem is when we live within these tribes the culture is so ingrained, we often don’t think about it or can struggle to express it.

Therefore, it is useful to have a model to examine and explain a culture. The Cultural Web, the tool developed by Johnson and Scholes, is a simple and effective lens to use in this context. Johnson and Scholes break down culture into six component parts: stories, symbols rituals and routines, power structures, organisational structure, and controls.

The Cultural Web

The Cultural Web comprises of the following components:

Stories

These are the past events people talk about. The shouted successes and the whispered failures. The discussions around the water cooler. These narratives carry important messages about the underlying values of a people group. The language used to express these stories – the jargon, acronyms, and lingo of a group – are just as important. Every tribe has its own dialect.

Symbols

These are not just flags, badges, and company logos. Symbols are also expressed in how people dress, office décor, even in a preferred brand of software and technology! Every item you see around you is the result of a choice influenced by a principle. For example, why have that type of coffee? Because it’s the highest quality, a trusted brand, or the best value? Understanding the decision can reveal a value judgement.

Rituals and routines

Every tribe has its own rituals and routines. The time when people start and finish work, what people do for lunch, even how (if at all) people celebrate birthdays and successes are all cultural rituals. Meetings are one fascinating way of examining culture. The routines of how a meeting is conducted, who sits where, who speaks when, and the language people use, all speak volumes about the culture and values of a group.

Organisational structure

There are always formal and informal structures in any group. Both need to be understood. An organisational chart may capture the official structure but what are the networks that exist, the webs hidden below those regimented lines? Look to see the tribes that gather; the smokers and the lunch-time runners as well as the project or function-based teams.

Power structures

Power derives from people and particularly the individuals who are decision-makers. These power structures do not always follow the official hierarchy either. For example, the personal assistant who manages access to an executive can wield power that outweighs their perceived grade in any management structure. Think: who are the internal influencers?

Controls

Controls are the systems, processes, and regulations that an organisation develops. These controls assist the conduct of work but also regulate behaviours. These can include things like financial controls, contracts, and company articles but there are also a host of unwritten rules and ways of working in any group. If you don’t think that is true, then just ask the newest member of the team about what they had to learn to be accepted into the clan.

Culture is manifest in behaviour

Once a culture is understood you can start to identify potential levers of change. But that still does not mean it is easy, if you don’t believe me just try changing the dress regulations for any given team!

We are all creatures of habit and therefore change at any level requires overcoming inertia. We all know this. Habits can be changed but think back to the last bad habit you tried to modify. It is not easy, even when you do identify the cues, routines and rewards in a habit loop.

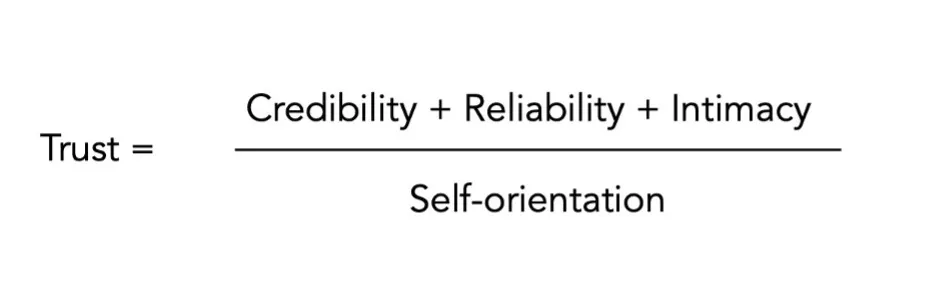

Therefore, even if the intellectual argument for change is compelling, there is a huge work to be undertaken once a strategy is agreed upon. As John P. Kotter shows in Leading Change, you must have leadership and a plan to take people through the change, not just set the target. To develop a plan, you need to understand the psychology of influencing groups of people and gently motivate them to act in the right way. This is the essence of nudge theory; people need subtle cues, personal incentives, and positive reinforcement to change.

How values should be expressed to inspire action

One way to engage a whole team or organisation in the change process is through a discussion of values. Values are symbiotic with culture, as it is our shared principles and corporate beliefs that are expressed in the symbols, structures, and stories that we share in an organisation.

The problem is the behaviour of many individuals and teams are not aligned to the stated values of their organisation. This is often due to one of these three problems:

The wrong values

Sometimes a company just picks the wrong values. The values are generally not bad in themselves – virtues such as creativity, inclusivity or productivity are all good – but that does not mean they are the right values for that given group or capture the drivers for change in a strategy.

Corporate values need to express the key beliefs of that given group. They express how that team makes decisions, how they are different and most importantly why they behave that way. If you want to change the priorities of an organisation, as happens in strategy implementation, then the values need to align with that strategy.

If this is the problem – and values do not express either the current situation or strategy – then it is worth starting again, examining culture, and engaging as many team members as possible to identify the true values of the organisation and the core principles of the new strategy.

Poorly expressed values

Expressing values poorly is the next common problem. This is often the case when companies choose single virtue words to communicate their principles. Take the word creativity. I have seen creativity stated as a value for schools, legal teams, and accountancy firms, not just the obvious ones such as advertising teams, tech firms and artists.

So, if you pick a term like creativity, the question is, what does that mean within your given context? One simple way to improve the expression of a specific virtue is by coupling it with another word. Creativity could become continual creativity, collaborative creativity, playful creativity, or something else. But suddenly, with just adding one (or two) extra words that value statement becomes more personal to the group and can better express the way that value informs choices and behaviours.

Misunderstood values

And that thought on behaviours brings us nicely to the third point – misunderstood values. Even if a value is expressed succinctly it may still need further explanation to describe how that value informs the actions of that group.

Therefore, when considering corporate principles (or personal values for that matter), once the value has been identified and expressed, the next step is to define its meaning in terms of how it informs action. Every value needs a paragraph of explanation that unpacks how a value should inform the thought processes and behaviours of the team.

Expressing organisational culture through shared values

So, don’t let your organisational culture eat your shiny new strategy for breakfast. If you want a strategy to succeed, having a good strategic plan is not enough. You need to bring strategy, culture, and values together. To do this you must:

- Understand the organisational culture

- Identify values that align that culture with the strategy

- Explain and demonstrate how those values should be expressed in behaviour and decision-making

This may not be a quick or easy process, but it is better to go slow than to race towards the strategy car-crash that is likely to happen if you try to enforce a change without following these steps. It is a thankless task – for managers and workers alike – to have to continually prod people to change direction.

But if a company’s strategy and values are aligned, and the team behaves according to those principles, then it is like a flywheel starting to turn. It builds up momentum to a point where the positive inertia pulls the organisation towards its goal. Then, as the boss, you can stop thinking about prodding and start thinking about what new ritual you might introduce to celebrate the success of the team!