Why every leader should know David Patreaus’ 4 stages of creating and Implementing Effective Strategy

Who can you think of who has genuinely created and implemented an effective strategy?

Plenty of people profess to have done this but few have accomplished this feat on the international stage or at the Grand Strategic level.

As we will see, from someone who actually has some credibility (no, I don’t mean me!), an effective strategy can be implemented in 4 steps.

But before we get onto this, what does strategy really mean anyway?

It is an overused term, and this can cause confusion. You might hear someone say, “My strategic approach is to…” and then list a series of goals. That is not a strategy. Neither is it the same as a mission or vision statement.

Strategy made simple

Strategy comes from the Greek word Strategos, which means military general. The General was the commander who gave the overarching directive to an army; the conceptual framework of how to defeat the enemy.

We might not be facing a real-life enemy, but we are sure to face challenges, which is why modern interpretations of strategy substitute these terms. For example, Richard Rumelt, author of Good Strategy, Bad Strategy defines strategy as

“A strategy coordinates action to address a specific challenge.”

In other words, it is the ends, ways and means of success, which itself is another good definition of strategy, still used by militaries today.

“Strategy equals ends (objectives toward which one strives) plus ways (courses of action) plus means (instruments by which some end can be achieved).”

Colonel Arthur F. Lykke Jr

Somewhat unsurprisingly, in terms of practical application, examples and theoretical principles, the military is still a primary source for the understanding of strategy. David Petraeus (retired US Army General) is a classic example of someone who has created and seen through an effective strategy at a genuinely strategic level.

Who is General David Petraeus anyway?

For those unaware, David Petraeus is a retired General, who commanded at the highest levels, and is also a former Director of the CIA. Suffice to say, having wielded that degree of power, he knows a thing or two about strategy.

Most importantly he knows how to implement one.

This is perhaps best illustrated by his time as overall commander of coalition forces in Iraq in 2007. The situation he inherited was certainly a strategic problem.

At the start of 2007, the US military was sustaining around 100 fatalities per month and around 700 wounded, while civilian casualties were around 1500 a month. Baghdad was effectively lawless and local militias as well as insurgents, of various ideologies, rampaged around the country causing mayhem.

Yes, I hear some of you say, this was a problem partly of the coalition’s making, and yes, there you have a point. In fact, the lack of a coherent long-term political strategy (beyond the military one) in Iraq was a large cause of this situation. But the challenge in 2007 remained, and General Petraeus was chosen to tackle the immediate issue of the horrific death rate.

The Surge Strategy in Iraq

After going through proper problem analysis, Petraeus developed the ‘Surge’ strategy. On the face of things, this could have been seen as just an increase in troop numbers, but it was a lot more than that. The plan recognised that previously the military had been using many wrong ways and means. It needed new ideas. Therefore, the surge was not just an increase of 30 000 troops but also encompassed new counterinsurgency (COIN) doctrine, changing the ways and means that would be used to stabilise the country (the ends).

The success of The Surge can be seen in numbers. Civilian casualties quickly reduced in 2007 and fatalities from mid-2008 to mid-2011 fell to around 200 a month. US fatalities dropped to fewer than 11 per month in the same period. Overall, the surge strategy resulted in nearly a ten-fold reduction of fatalities from 2006 figures.

Defence Secretary Robert Gates described Patreus’ ‘Surge’ campaign in Iraq in 2007 as the

“Translation of a great strategy into a great success in very difficult circumstances.”

Patraeus after the Surge

Petraeus did implement a successful strategy in Iraq but that does not make him perfect. He, like any senior leader, did not always succeed (he was not quite able to replicate the success of Iraq in Afghanistan due to the vastly different circumstances) and he messed up badly too (Petraeus had to step down as director of the CIA after it was revealed he was having an affair with his biographer).

As well as recognising that these failings just make Petraeus human, he is easier to respect in the aftermath as he has been willing to admit and address his faults (a virtue not seen in some very senior figures).

Petraeus, though nominally retired, is still very active. He is a visiting professor to prestigious universities across the world, and, due to his strategic wisdom, serves as an advisor and board member to multiple diverse organisations. So, even with his faults, his strategic mind is still highly valued.

Therefore, when he says something about strategy, I take note. Recently, he shared his four steps to developing an effective strategy at the Royal United Services Institute (the defence and security think-tank) and so I thought I would share these and some reflections upon his framework.

The 4 Steps of Developing a Highly Effective Strategy

Patreus describes the following four steps as his “intellectual construct for strategic leadership.” In other words, this is not just about creating a strategy, or having the leadership to implement one, it is both combined.

Task 1: Brainstorming

The first step is to get the big ideas right, and that is dependent upon understanding the problem. The problem is made up of various factors too, such as mission analysis (assessing what you must do) and situational analysis (getting a deep understanding of the circumstances).

You have a better chance of analysing the problem and coming up with novel solutions if you have real cognitive diversity. Petraeus sought out scholars and deep thinkers to help him with this problem analysis. This included people who would challenge ideas. This is vital as a leader surrounded by sycophants will eventually come undone from hearing what they want to hear rather than what they need to hear.

Once problem analysis is complete then the brainstorming can enter a phase of creating options or courses of action. Options are then evaluated, and the leader (commander) makes their decision of which course of action they want to pursue.

So, the key question for a leader at this stage is:

How can you create the best team to understand the problem and come up with creative solutions?

Task 2: Communicating

Once the leader has decided upon the preferred course of action, that big idea can then be communicated. Now the challenge is working out who you need to communicate to and how.

There may be many stakeholders inside and outside the organisation that need to hear the message. In the case of Petraeus, during The Surge it was not just the soldiers who needed to know the strategy; it was everyone from the Pentagon in the US and coalition partners, right through to the local population and insurgents.

And each stakeholder group has different information needs and so an engagement strategy becomes a sub-set of the overall strategy. This includes stakeholder mapping and thinking about how each group needs to be informed and what influence you want.

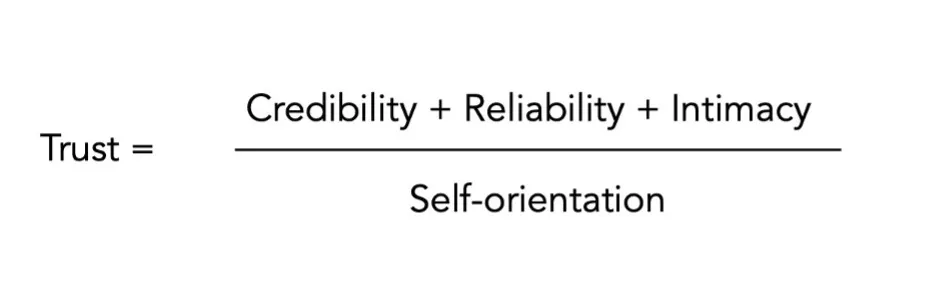

For example, Petraeus wanted to communicate with the local population and the end result was that he wanted trust and support – rather than hostility – so he needed to achieve a shift in mentality. Even for the coalition forces there needed to be a shift in mentality as they were going to have to change how they were going about their operations up to that point.

So, communication needs to be clear, as concise as possible and targeted to get people engaged and, where possible, empowered to support the strategy. When you are thinking of how to deliver the message a good starting point is The Rule of 3, which provides an easy structure to follow.

Therefore, the key question for the leader at this stage is:

Whom do I need to inform, how do I best communicate and what is the impact I want to have?

Task 3: Implementing

Once communicated, the next stage is implementation. This requires breaking down the big idea into an action plan. In military terms, this is the campaign plan where different lines of effort work together to achieve the desired end state.

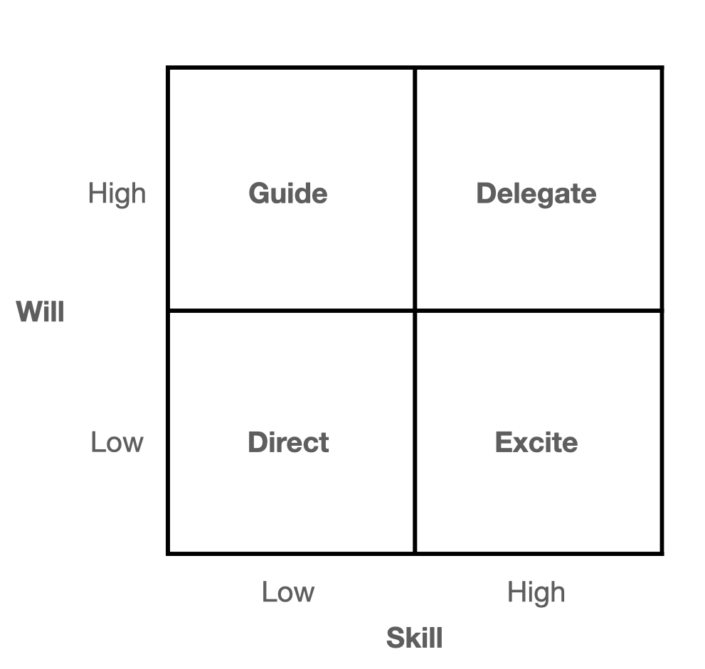

But a good plan is not enough on its own. Effective implementation requires good leadership. The strategic leader knows how to adapt their style to best influence each team member or stakeholder. For example, influencing sceptics might require a more transactional approach as they might not buy into the vision of transformational leadership. So, the principal needs to be able to apply situational leadership whilst remaining authentic.

As with the brainstorming stage, the strategic leader needs a great team around them for the best chance of success. Being a strategic leader means selecting and supporting the right champions to lead each element of the plan.

Therefore, for implementation, the leader needs to ask:

How do I turn this strategic idea into an actionable plan and who can best realise each element?

Task 4: Assessing

Never assume a plan is set in stone. As Field Marshall Helmuth von Moltke stated:

“No plan survives contact with the enemy.”

In other words, it does not matter how good your idea is, when that plan interacts with the real world (and the many factors you could never foresee) the strategy will need to evolve.

We live in a rapidly changing world. Good leaders expect to refine their strategy is this VUCA (volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous) environment. What’s more, the ability to assess how effective a strategy is, and then adapt plans to improve them, is the mark of a high-performing team as well as a great leader.

A high-performing team retains a growth mindset, learns from failure and drives their continual improvement by constantly assessing what to start, stop or continue within the given plan.

Therefore, for the leader at this stage, the critical question becomes:

How do we improve the plan and reinforce success; what do we need to start, stop, or continue doing?

The Strategic Cycle: How to Create and Implement an Effective Strategy

David Petraeus’s strategic framework is very simple on the surface. The four stages of brainstorming,communicating, implementing, and assessing, create an easy-to-remember cycle.

And strategy is cyclical. One situation and set of effects lead to another. This was particularly true for Petraeus who went from overseeing The Surge in Iraq to being the commander in Afghanistan. This was a very different set of circumstances but one impacted by his own strategy in Iraq (namely the draw of resources from one area to another).

You may not be playing on the world stage but whatever level of leadership you aspire to, this strategic cycle can help you. Even if you are just working on your own and facing some big problem, the stages still hold true.

So, think, what is the biggest challenge you are facing right now? What can you do to brainstorm new ways of addressing the issue? What do you need to communicate? How will you best implement the plan to resolve the issue and how can you keep assessing your progress?